Pushkin House exhibition ‘Russian Types & Scenes’

Wednesday, May 13th, 2015

Swan Lake, Vytegra, August 2014

Snowflake, Kargopol, August 2013

19th June â 20th September 2015, Private View 18th June, 7pm.

Swan Lake, Vytegra, August 2014

Snowflake, Kargopol, August 2013

19th June â 20th September 2015, Private View 18th June, 7pm.

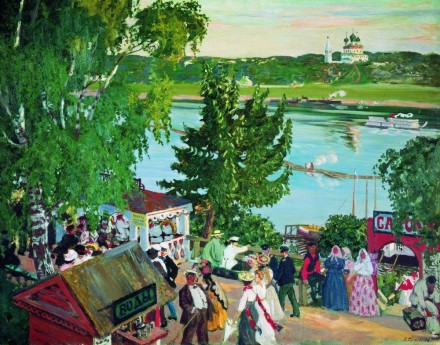

This painting ‘Promenade along the Volga (Romanov-Borisoglebsk)’ was painted by Boris Kostudiev (1878-19270) in 1909. In 1918, Romanov-Borisoglebsk was renamed in memory of the Red Guard I P Tutaev, who was killed in the Yaroslavl revolt of 1918. Tutaev is the home of the Shuvalov Bell Foundry. On the 30th of March this year the bell foundry cast six bells for the bell tower of the Church of the Transfiguration in Turchasovo.

Tutaev March 2015

Alexander Mozhaev wrote the following about Tutaev and bell making for ‘Russian Types & Scenes’. . . The main street on the Romanov side of Tutaev, a town that straddles the Volga upriver from Yaroslavl, leads to the gates of the famous Shuvalov Bell Foundry. There had been no church bell foundries in Russia since the upheavals of the 1930s when the Soviets destroyed both the means and the know-how for producing bells. Nikolai Shuvalov was, until 1992, a gas pipeline engineer. He explains his decision to resurrect the art of bell making in Russia very simply: âIn the late eighties, when there was no life left in the pipeline business, I started freighting in fruit and vegetables from the south and managed to make enough money to put some aside. Although there was hardly an intact bell tower in the country I decided to put my money into bells, maybe because no one else was. After ï¬ve or so years of experimentation I started to produce decent bells, then the ï¬ood gates opened and the orders started ï¬owing in.â

Pouring the metal

To a layman, the manufacture of a Russian bell looks impossibly complicated â like writing with both hands while looking in the mirror. A bell is like sculpture cast in metal, it has to be fashioned, or rather, its opposite has to be fashioned with great skill and precision. Each bell is made from scratch and each bell has its own unique sound.

The knowledge that most of us have about the mysteries of Russian bell casting is nil, and any knowledge we do have comes from the bell making chapter in Tarkovskyâs extraordinary ï¬lm Andrei Rublev. A young lad, who claims to have inherited the secret of bell making from his father, is commissioned to cast a colossal bell for the Grand Duke. The undertaking is on a gigantic scale. He tells the agents of the Prince âWe need more silver, tell the Prince not to be so stingy, we need another half poodâ â âIf we donât youâll get a beam, not a bell.â â âWho knows the secret of bell bronze? You or me?â As an aside, to his assistant he laughs and says âIâm going to shake a load of silver out of the Prince.â

The cast is broken open

No expense is spared it seems! But it isnât silver being thrown into the furnace, it is tin. Shuvalov explains, âBronze is an alloy of copper and tin, and at that time Russia imported much of its tin from England. But the English, as always, found a ruse to maximise their proï¬ts and they would only sell tin in the form of tableware â thereby adding a hefty premium. So Tarkovskyâs scene is pretty accurate, with its armfuls of white metal utensils being thrown into the furnace. The bell founders ï¬eeced their clients by demanding more and more silver. This was kept safe in the ï¬rebox and later raked out with the ashes.â

One of the newly cast bells

Maybe this story is nonsense but there is an old Russian saying âPouring bells!â (Ðолокол лÑÑÑ) which means telling ï¬bs and lies. As the old custom tells, creating a buzz in the crowd by spreading scandalous gossip during the casting, guarantees that the bell will sing!

Alexander Mozhaev, 2014

I’m pleased to record that much scandalous gossip was spread during the casting of the Turchasovo bells, in fact many words where used which Natasha Shalina, our interpreter from St Petersburg, refused to translate. A clue was given by her flushed cheeks and giggles!!